Georgia Tech scientists get first look deep under Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier and Kamb Ice Stream

ANTARCTICA — An international team including scientists from Georgia Tech captured new images and first-of-its-kind data from deep beneath an Antarctic glacier, which will help scientists to better understand the impact of one of Antarctica’s fastest changing regions and its impact on future sea level rise.

Their work will be featured as part of a special report on BBC World News on Tuesday, Jan. 28, in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the discovery of Antarctica.

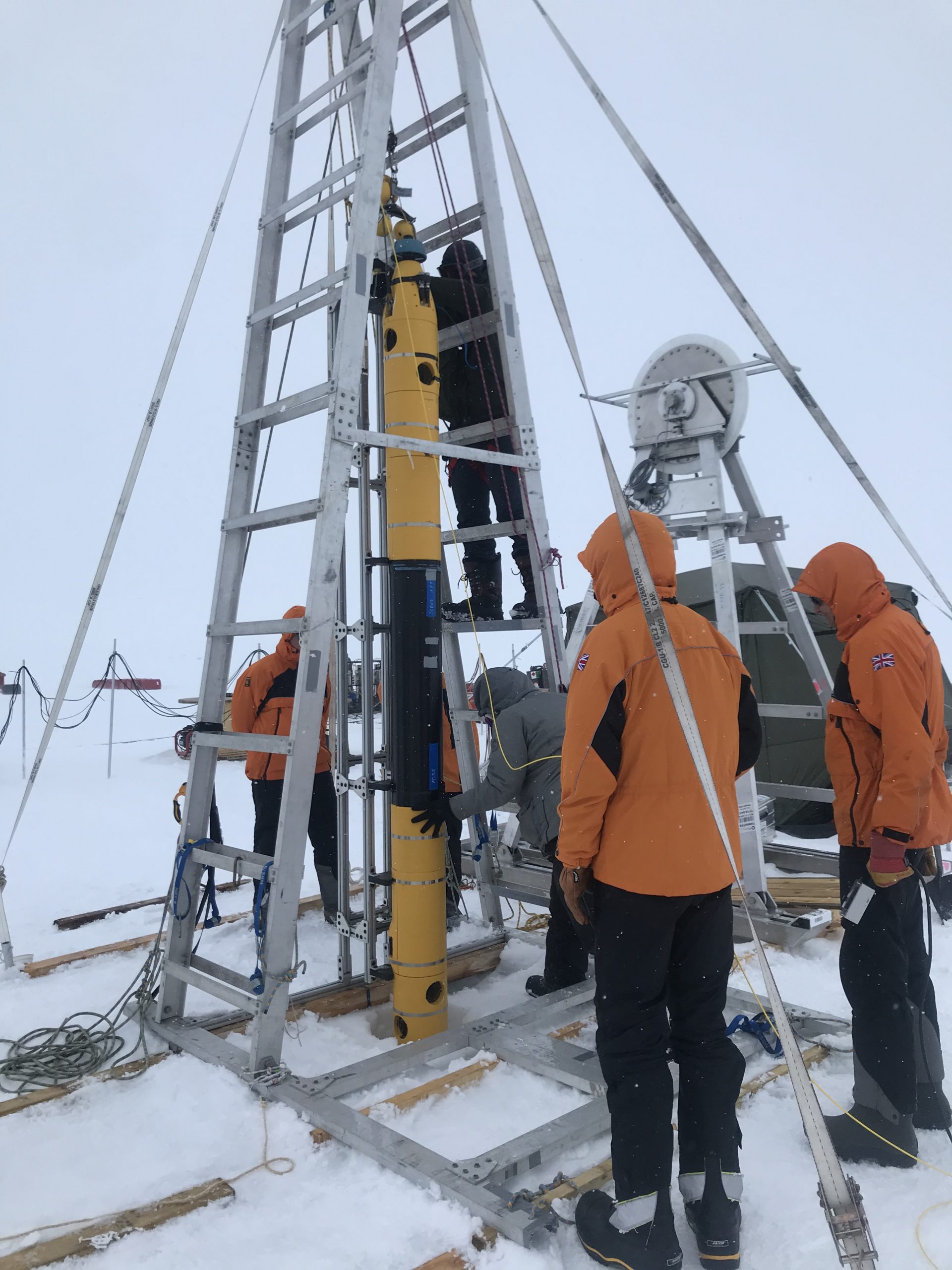

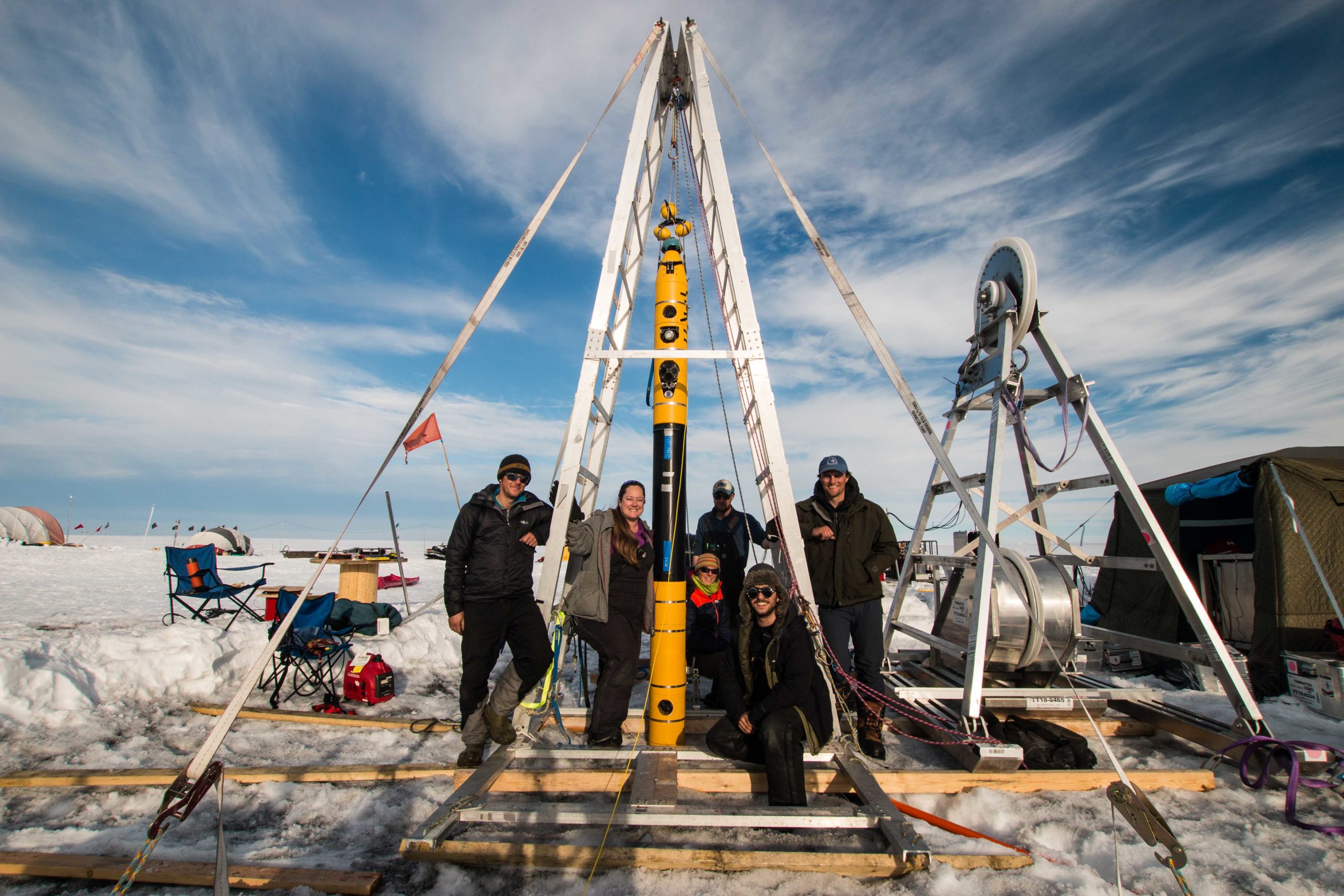

Stationed in Antarctica for the last two months, the MELT (Melting at Thwaites grounding zone and its control on sea level) team, part of the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, deployed ocean instruments and cored sediments to gather data on one of the most important and hazardous glaciers in Antarctica. The MELT team included Georgia Tech scientists who used an underwater robot named Icefin to navigate the waters beneath Thwaites Glacier and collect data from the grounding zone – the area where the glacier meets the sea.

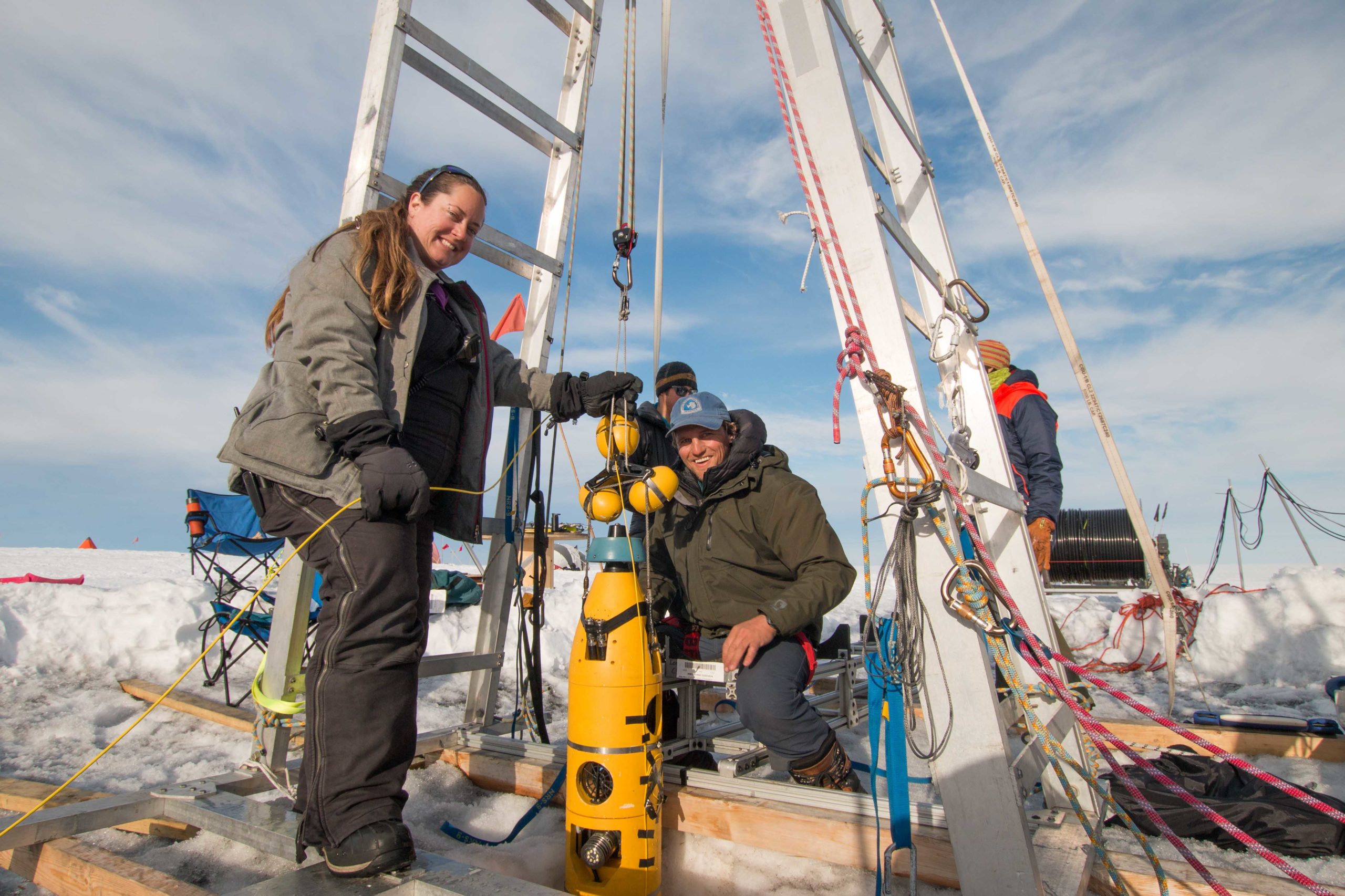

Dr. Britney Schmidt, lead scientist for Icefin and associate professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, said the new data represented several firsts for her team, as well as for science as a whole.

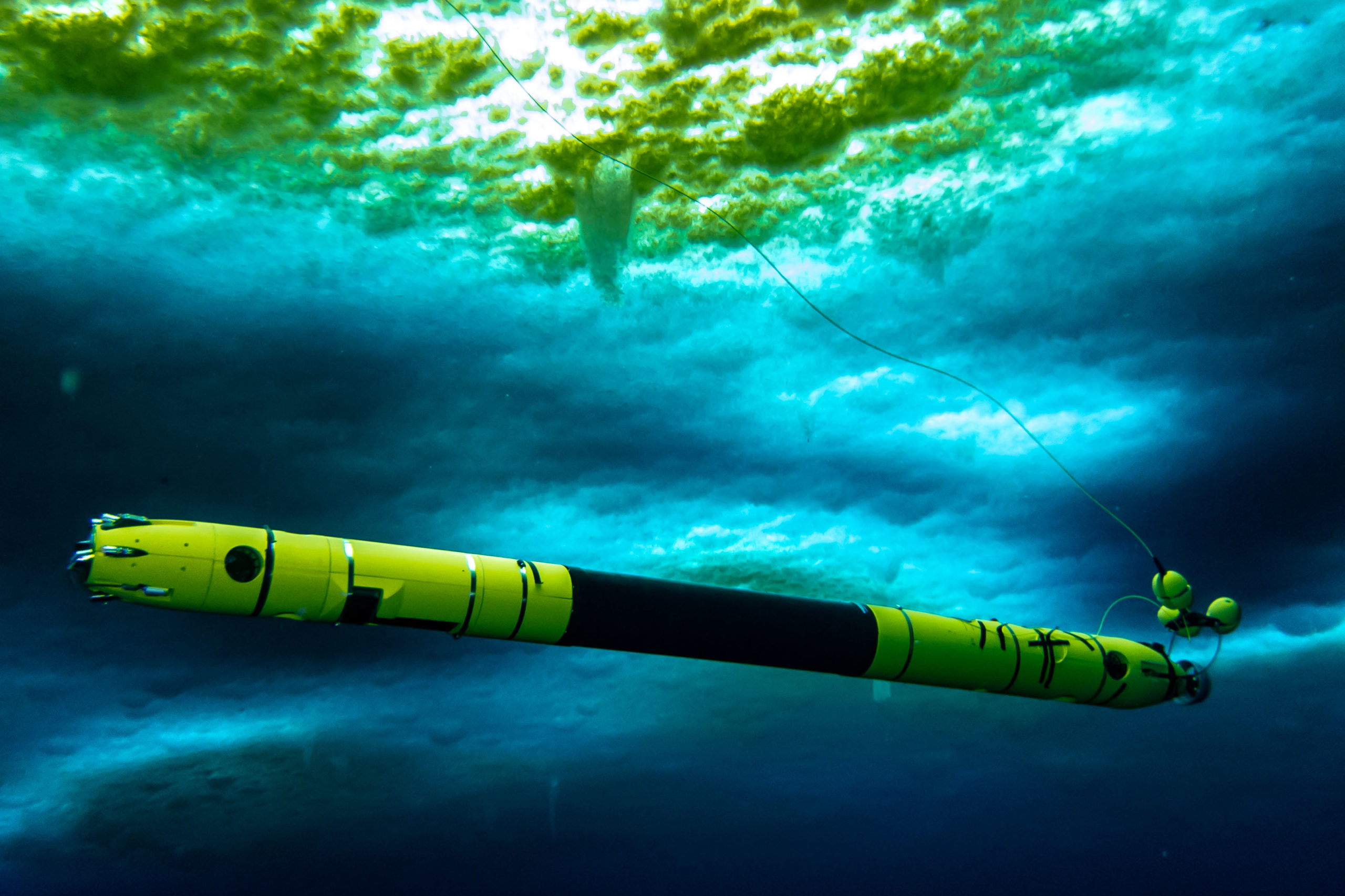

“We designed Icefin to be able to finally enable access to grounding zones of glaciers, places where observations have been nearly impossible, but where rapid change is taking place,” said Schmidt, a co-investigator on the MELT project. “We’re proud of Icefin, since it represents a new way of looking at glaciers and ice shelves. For really the first time, we can drive miles under the ice to measure and map processes we can’t otherwise reach. We’ve taken the first close-up look at a grounding zone. It’s our ‘walking on the moon’ moment.”

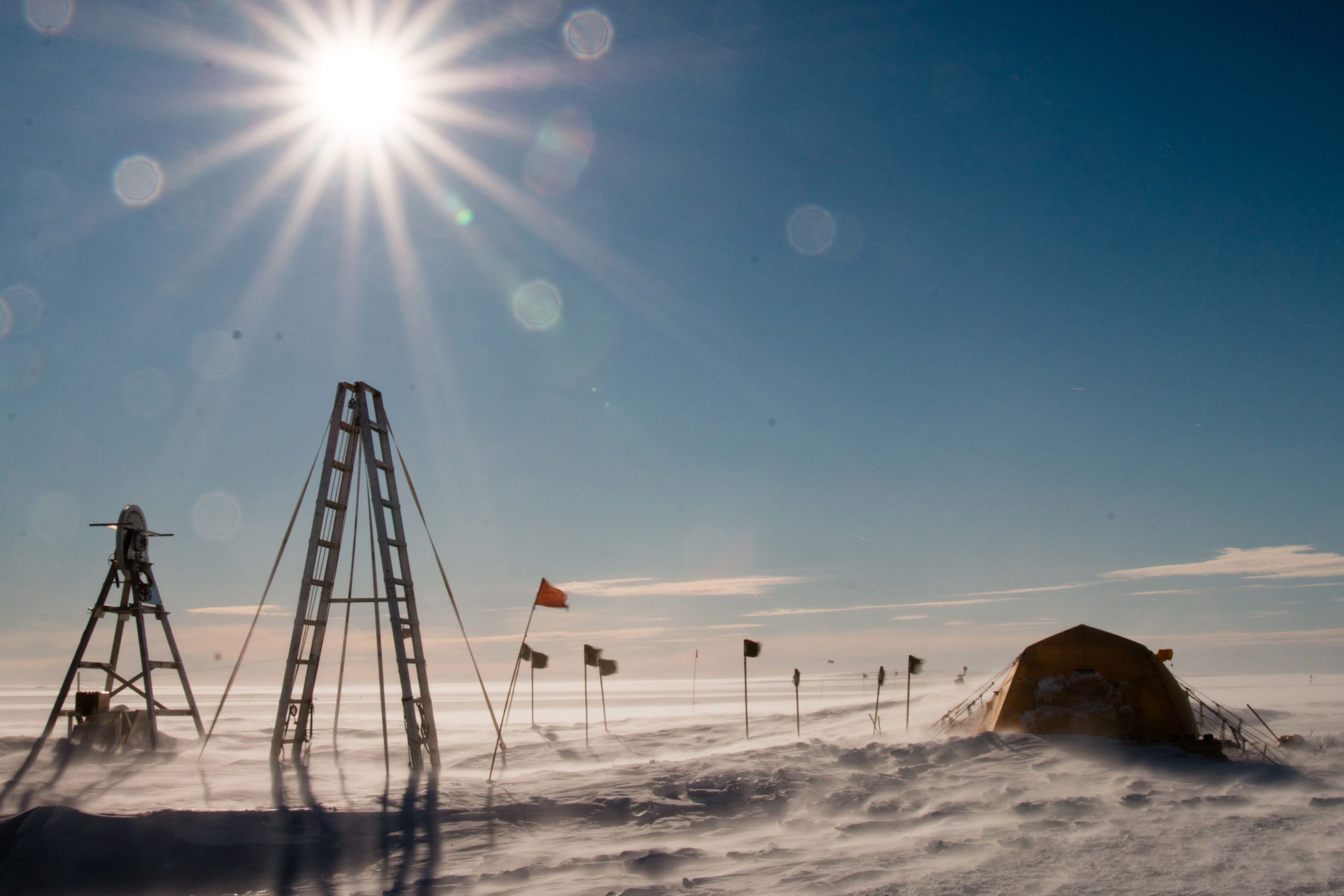

Located in a remote part of Antarctica, where few scientists have ever ventured, the team battled sometimes hostile weather, extreme winds, and temperatures below -22 degrees Fahrenheit to get close enough to the Antarctic coastline for Icefin to reach the grounding zone.

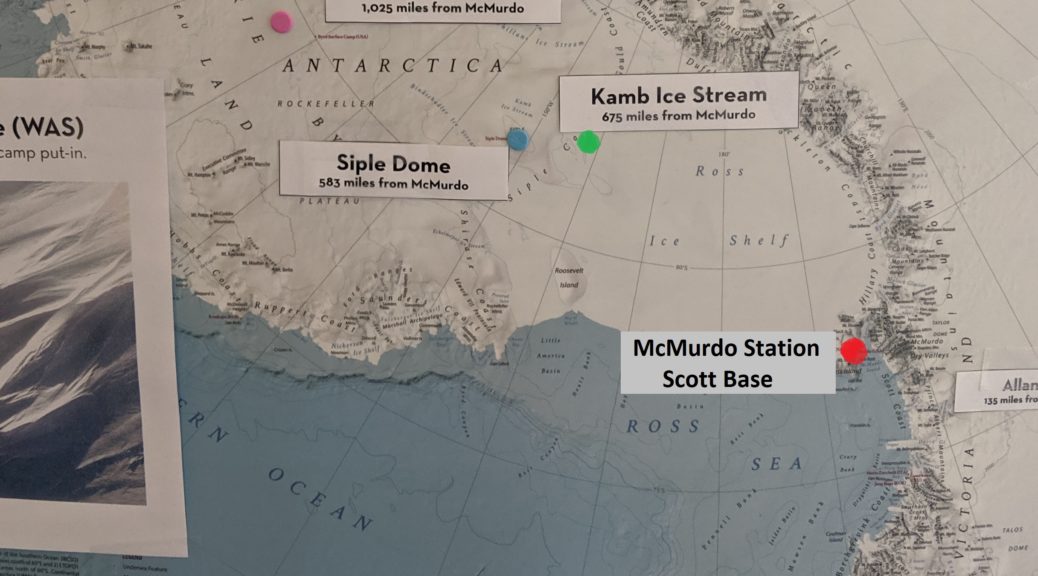

In these trying conditions, the MELT team used hot water to drill through up to 2,300 feet – nearly a half mile – of ice to get to the ocean and the seafloor below. On Jan. 9 and 10, Icefin swam more than a mile from the drill site to the Thwaites grounding zone, to measure, image, and map the glacier’s melting and gather other important data that scientists can use to understand the changing landscape and conditions. Not only did the team put one Icefin robot down the borehole at Thwaites Glacier, but they did it with a second Icefin vehicle in collaboration with Antarctica New Zealand near the grounding zone of Kamb Ice Stream, part of the Ross Ice Shelf.

Thwaites Glacier, which covers an area the size of Florida, is particularly susceptible to climate and ocean changes. Thwaites melting accounts for about 4 percent of global sea level rise, and the amount of ice flowing out of Thwaites and its neighbouring glaciers has nearly doubled in the past 30 years, making it one of Antarctica’s most rapidly changing regions.

Dr. Keith Nicholls, an oceanographer from British Antarctic Survey and UK lead on the MELT team, said Icefin’s exploration of sediment and other conditions in the Thwaites grounding zone will help scientists determine how this region will change in the future and what kind of impact on sea level rise we can expect from these changes. The MELT team also deployed radars and oceanographic sensors, conducted seismic studies and took sediment cores from beneath the glacier, and deployed two moorings through the ice that will record ocean and ice conditions for the coming year to monitor changes at Thwaites.

Dr. Keith Nicholls, an oceanographer from British Antarctic Survey and UK lead on the MELT team, said Icefin’s exploration of sediment and other conditions in the Thwaites grounding zone will help scientists determine how this region will change in the future and what kind of impact on sea level rise we can expect from these changes. The MELT team also deployed radars and oceanographic sensors, conducted seismic studies and took sediment cores from beneath the glacier, and deployed two moorings through the ice that will record ocean and ice conditions for the coming year to monitor changes at Thwaites.

“We know that warmer ocean waters are eroding many of West Antarctica’s glaciers, but we’re particularly concerned about Thwaites,” he said. “This new data will provide a new perspective of the processes taking place, so we can predict future change with more certainty”

The MELT project is funded by the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC), a collaboration between the U.S.’s National Science Foundation and the UK’s Natural Environment Research Council.

“To have the chance to do this at Thwaites Glacier, which is such a critical hinge point in West Antarctica, is a dream come true for me and my team. The data couldn’t be more exciting,” Schmidt said. “And exploring the grounding zones of two different glaciers in the same season is incredible.”

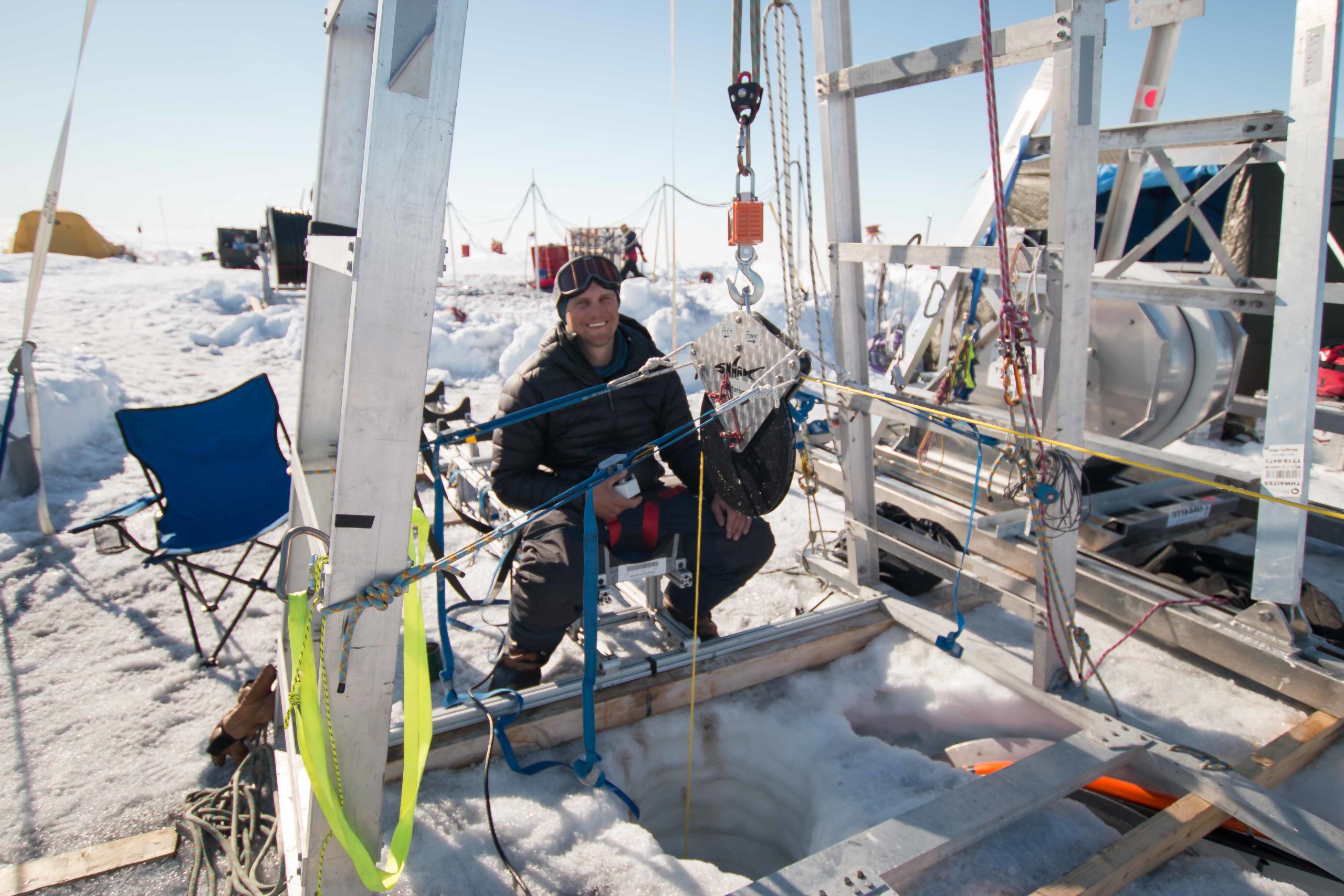

In addition to the MELT project, Schmidt is the Primary Investigator for the RISE UP (Ross Ice Shelf and Europa Underwater Probe) project, which also had team members from Georgia Tech deployed in Antarctica this season. RISE UP is a NASA-funded project that developed Icefin from a prototype to a full-fledged underwater vehicle and aims to develop technology for future missions to Jupiter’s moon Europa.

Both the MELT and RISE UP teams spent time at McMurdo Station, Antarctica conducting research, before simultaneously deploying to more remote areas. Antarctic logistics for both projects were supported by the National Science Foundation, under the United States Antarctic Program.

RISE UP‘s work at Kamb Ice Stream came as part of a collaboration with two projects supported by Antarctica New Zealand: the NZARI Ross Ice Shelf Programme led by Dr Christina Hulbe of the University of Otago, and the NZ Antarctic Science Platform’s Antarctic Ice Dynamics project, led by Dr Huw Horgan of Victoria University.

RISE UP team members deployed along with the New Zealand hot water drilling and science teams to study the Kamb Ice Stream – a river of ice – on the Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica. Their goal was to explore and map areas near the grounding zone to better understand its flow and the surrounding environment. Icefin’s work at Kamb Ice Stream will continue next season as part of Dr. Horgan’s project.

“We now have, effectively, a transect of conditions from the front of the Ross Ice Shelf to the grounding line,” sadi Christina Hulbe of the Ross Ice Shelf Programme, which finished its final year of field work in late December. “In addition to Icefin’s work, we’ve installed our third ice-anchored mooring, collected cores for sedimentary and microbiological analysis, we’ve imaged the ice optically and using radar, and made high resolution observations of ocean conditions.”

The RISE UP team completed three dives with Icefin, and team member Ben Hurwitz, a graduate student at Georgia Tech who works on Icefin’s technology, said the season was wildly successful, adding the team was “excited to share what we found in the coming months.”

Notes on the projects:

The International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration: www.thwaitesglacier.org

The MELT Project is lead by Keith Nicholls , an oceanographer with the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), and Dr. David Holland, an applied mathematician (with a background in fluid dynamics) at New York University, with co-leads Dr. Eric Rignot from the University of California at Irving, Dr. John Paden with George Mason University, Dr. Sridhar Anandakrishnan out of Pennsylvania State University, and Dr. Britney Schmidt at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

RISE UP’s field work at Kamb Ice Stream came as part of two science projects funded by Antarctica New Zealand and the Victoria University of Wellington Science Drilling Office. The other research partners involved on the project are: The University of Otago, Victoria University, University of Canterbury and University of Waikato, NIWA and GNS Science from NZ and the ROSETTA project and Universty of California, Santa Cruz in the US.