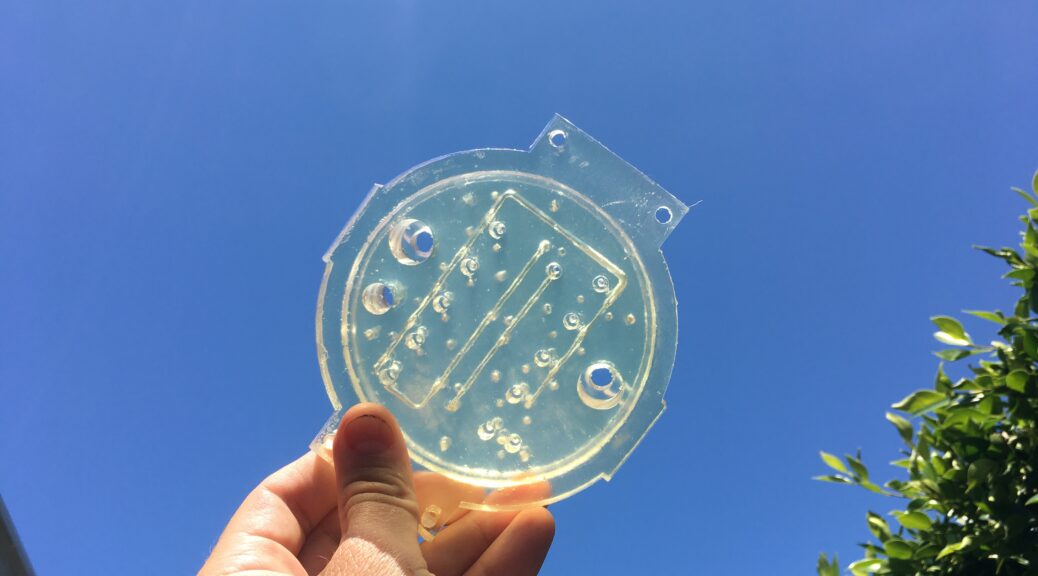

Icefin is an underwater oceanographer robot with projects funded by the likes of NASA and the National Science Foundation, and helps scientists explore ice-covered oceans. Icefin may be the inspiration for future trips to Jupiter’s icy moon Europa, which is a key target on NASA’s list for ocean world exploration that could potentially harbor life.

Right now, Icefin vehicles are being used to study things like glaciers and ice streams in Antarctica. Whether mapping the underside of glaciers on Earth, or paving the way for ocean exploration on other worlds, Icefin is doing some seriously ground-breaking (or should we say, ice-breaking) work!

Here’s why Icefin should be your new favorite robot:

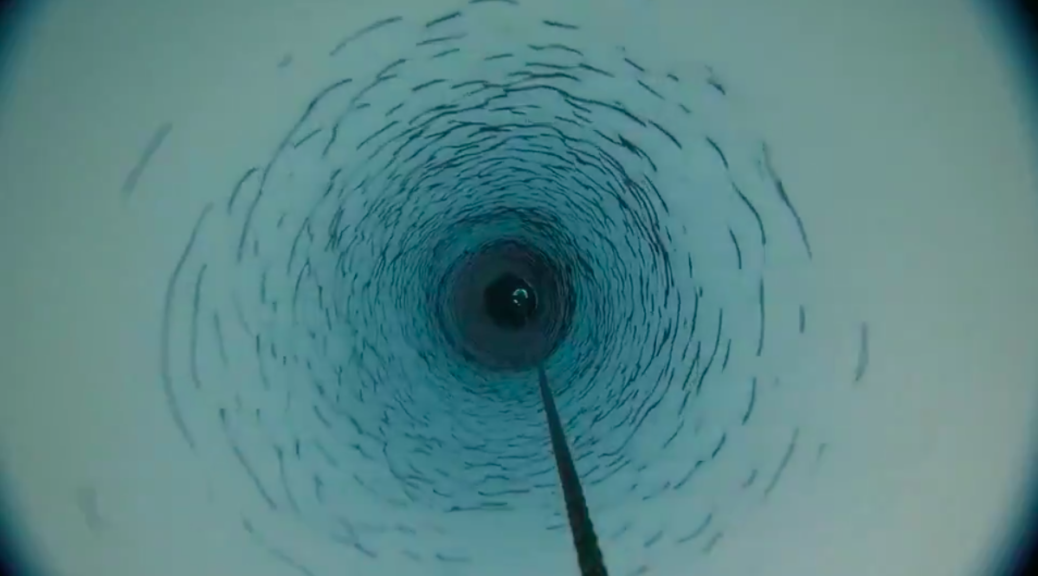

- Icefin has gone where no robot (or person) had gone before. “This is one small step for Icefin robot, one giant leap for robotkind”. During the 2019-2020 field season in Antarctica, Icefin was the first robot to deploy through a borehole drilled through a half mile of glacial ice, into the cold ocean beneath, and travel miles beneath the ice to map, measure, and study the underside of the critical Thwaites Glacier. Another Icefin vehicle, during the same season but in a different location, entered the ocean below the ice of Kamb Ice Stream, part of the Ross Ice Shelf, and explored that environment like never before. By going to places we had never been on Earth, Icefin robot will help lead us to places we’ve only dreamed of.

- Icefin will help scientists who study climate change, oceans, and glaciers, to more accurately predict our future. You care about climate change. That’s one of the reasons why we hope you’ll care about Icefin like we do. The robot oceanographer is helping scientists get a more detailed understanding of glaciers (like Thwaites, also known as the Doomsday Glacier because of its size and potential impact if/when it collapses). By collecting first-of-its-kind data and images of the underside of glaciers, both stable and eroding ones, we can paint a clearer picture of how and why they change, how fast it’s happening, and what impact we might see as these glaciers change.

- Icefin has some killer media. You know you love those aesthetic photo posts, whether it’s gorgeous vacation #goals on Facebook, or that astronomy pic of the day Instagram feed. Icefin will add an underwater, otherworldly, cool (see what we did there) aesthetic to your social feed. Want to see content like this, or this, or this, or this? You know what to do, follow Icefin (on social media) to where no robot oceanographer has gone before!

- Icefin is laying the groundwork with exploration on Earth, so future robots can explore other worlds. Speaking of “where no robot has gone before”, by exploring icy oceans in Antarctica, Icefin is paving the way for future robotic missions to other worlds with ice-covered oceans in our solar system, like Jupiter’s moon Europa. The moon is believed to have a vast liquid ocean covered in a layer of ice, which could harbor life, and robots like Icefin (and next generation vehicles) will be the ones to explore those alien landscapes, which may in fact look a lot like our own polar waters.

- Icefin is backed by a team of awesome people. We like to work hard and do science, engineering, and programming… and we like to have fun. We’re down-to-Earth people (unfortunately not down-to-Europa, yet!), and we promise you won’t regret making Icefin your favorite robot. Want to learn more? Check out this awesome short film NOVA Science made about us!

And there you have it! Now that Icefin is your new favorite robot, go follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and our blog, and check us out online!